Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Text this colour are links that disabled for Guests.

Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page.

Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker of Swinbroke

Baker was a secular clerk from Swinbroke, now Swinbrook, an Oxfordshire village two miles east of Burford. His Chronicle describes the events of the period 1303-1356: Gaveston, Bannockburn, Boroughbridge, the murder of King Edward II, the Scottish Wars, Sluys, Crécy, the Black Death, Winchelsea and Poitiers. To quote Herbert Bruce 'it possesses a vigorous and characteristic style, and its value for particular events between 1303 and 1356 has been recognised by its editor and by subsequent writers'. The book provides remarkable detail about the events it describes. Baker's text has been augmented with hundreds of notes, including extracts from other contemporary chronicles, such as the Annales Londonienses, Annales Paulini, Murimuth, Lanercost, Avesbury, Guisborough and Froissart to enrich the reader's understanding. The translation takes as its source the 'Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke' published in 1889, edited by Edward Maunde Thompson.

Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback format.

Annals of Winchcombe and Sudeley by Emma Dent is in Prehistory.

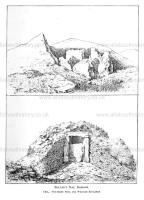

Belas Knap [Map] barrow was opened in 1863. It presented all the interesting features of the long tumuli of the Britons; the cromlech to the north, and sepulchral chambers at the east and west; also a single sepulture, in a grave constructed of rough stones, at the south, possibly a later interment. The walls leading to the entrance of the barrow were constructed of stones unhewn and unchiselled; the stones of the entrance also were without any mark of instrument upon them. It seems as if the sacredness of the spot was esteemed to be enhanced by this absence of workmanship with metal, as in Scripture times: "An altar of earth thou shalt make unto me .... and if thou wilt make me an altar of stone, thou shalt not build it of hewn stone: for if thou lift up thy tool upon it, thou hast polluted it." Exod. xx. 24, 25.

Flint implements were found in the barrow; the one represented in the opposite Plate in all probability was the sacrificial knife; and from its calcined condition most probably was thrown into the fire with the sacrifice. Flint knives are frequently mentioned in Scripture; the priests of Baal cut themselves with flints; they shaved themselves with them as a sign of mourning; and both in the true and the false religions of primitive times such implements were constantly used in their religious or superstitious ceremonies. Unfortunately no trouble was bestowed on the preservation of this barrow; consequently the principal cromlech on the N. side was broken and the sepulchral chambers destroyed; but a valuable collection of skulls gathered therefrom is preserved in the College Museum at Cheltenham, of which a very interesting description is given in "The Proceedings of the Socicty of Antiquaries, April 19, 1866," where the progress of the excavations is described, from a report by L. Winterbotham, Esq.; but we must content ourselves with a slight notice of the results.

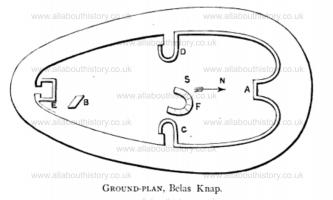

Beginning with A in the ground plan, on a large flat stone nearly eight feet square and two feet thick, was discovered a massive lower jaw, and under the stones, the bones of five children from one to seven years of age. There were no remains of an adult, but one remarkable male skull, which might pass for a well-developed modern head. In cell B were found human bones, with the bones and tusks of boars, a bone scoop, some picces of rough sun-dried pottery, and a few flints. C represents an area of about five feet, originally roofed in with large slabs of stones, but which had given way and fallen upon twelve skeletons placed round in a sitting position on flat stones—these were partially pressed into the ground from the weight above them. In the nostrils of the skulls were parts of the fingers, as if, in the sitting posture, the fingers had so been placed as to keep the head erect. D contained fourteen human skeletons, with no other remains but the bones of mice, found chiefly in the skulls, E contained part of a human skull and bones of a wild boar, both bearing marks of cremation. F was a broken circle of stones, seven feet in diameter, but with no remains. The soil around was deeply impregnated with wood ashes, and here was found the calcined knife. In all, thirty-eight skeletons were found.

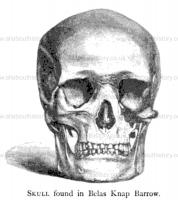

Among the skulls, the most remarkable is the one here delineated, showing how the upper incisors were broken off, or ground down even with the gums. Other lower jaws exhibited the same peculiarity. It remains for future archaologists to ascertain whether this was but a fashion, or a badge of distinction among the men who tenanted our hills in those far-off prehistoric times. In "Crania Britannica," by Davis and Thurnam, these skulls are tabulated and described, as they are considered to form a valuable and complete collection of very interest- ing ethnological specimens. Many of the arrow heads and flint imple- ments in the Sudeley Collection were found in the immediate vicinity of this barrow.

Geologists tell us the stone age takes us back thousands, perhaps millions, of years, when the configuration of the globe differed from what it is now; when mankind dwelt on the earth with animals long ago extinct, with the mammoth and the woolly-haired rhinoceros, and innumerable others. The study of those remote periods has become a science; and the earnest searchers after truth, doubtless having found "some foot-prints on the sands of time," will gradually so track them back, that fields of knowledge will yet be discovered of which we of to-day have no idea, and when possibly even the connection between history and geology will be made clear. It is easy to imagine that the philosophers of future ages may smile at ours of to-day, even as we smile at those of early times, when it was believed that fossils were serpents and such like turned to stone by saints—at least such was the teaching of the monks; and Fuller, some centuries later, is almost as extravagant. He says,1 "Who knows not, but at Alderly, in Gloucestershire, there are found stones resembling cockles or periwinkles in a place far from the sea, which are esteemed by the learned the gamesome work of nature, some time pleased to disport itself and pose us by propounding such riddles to us."

Note 1. "Church History of Gloucestershire".

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

But to return to comparatively modern times. The worship of Bel originated with the Assyrians, to whom the Pheenicians owed their origin; and as the Phanicians came here at a very remote period trading for tin, it is not difficult to see the connecting link between the introduction of their faith into this Island, and the origin of the name Belas Knap. This barrow very greatly corresponds with the description given by Sir John Lubbock1 of the tumuli of Northern Europe, as consisting of large mounds, with a passage formed by blocks of stone leading into a central chamber in which sit the dead, exactly like the arrangements of the hut in which the Esquimaux of the present day pass the winter. Professor Nilsson concludes from this, that the graves were built after the pattern of the dwelling-houses, or that in some cases the very house in which the dead man had lived was converted into his grave. He says that some of the ancient tribes of the North, unable to imagine a future altogether different from the present, showed their respect and affection for the dead by burying with them those things which in life they had valued most; with ladies their ornaments, with warriors their weapons. When a great man died, he was placed on his favourite scat, food and drink were arranged before him, his weapons were arranged at his side, and the house was closed and the door covered up, sometimes, however, to be opened again when his wife or children joined him in the land of spirits.

Note 1. Antiquity of Man.

Though more rare in England than in Scandinavia, our tumulus by Humblebee Wood must have been of this kind. Some antiquaries have gone so far as to suppose that the contents of these barrows indicate "a belief in a future state, and of some doctrine of probation and of final retribution," but to this Sir John Lubbock, in the lecture before quoted, does not assent. Yet as we turn from contemplating these bones so recently brought forth from the long-forgotten and unnoticed barrow, what a mysterious and sacred atmosphere seems to veil their history from our eyes!

That mighty heap of gathered ground!" Who can tell what love and devotion may not have worked to raise that mound; what grand religious rites and ceremonies may not have accompanied its completion; how may not the workmen have thought their work would last to all eternity, and the names of those so reverently placed within could never be forgotten!

"The mound is now a lone and namelgss Barrow,

Dust long outlasts the storied stone;

But thou—thy very dust is gone!"