Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Text this colour are links that are disabled for Guests.

Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page. Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

Archaeologia Volume 42 1869 Section IX is in Archaeologia Volume 42 1869.

On Ancient British Barrows, especially those of Wiltshire and the adjoining Counties. (Part I. Long Barrows). By John Thurnam, Esq. M.D., F.S.A., Local Secretary for Wiltshire. Read December 12th, 1867; February 20th and 27th, 1868.

Orientation.—As to their position in regard to the cardinal points, at least two out of three lie due east and west, with their chambered ends, which are usually the highest and broadest, to the east. This definite orientation, however, may have been equally intended in those barrows which point to the south-east rather than to the east or north-east; and the deviation, if not accidental, may imply that such barrows were erected during the winter solstice. If these be regarded as pointing eastward, then we count four out of every five as having a definite orientation. In about one out of every five, however, the mound lies distinctly north and south; and, as regards these, it is observable that in some the chambered or broad end is to the north, in others to the south. Exactly the same variety of arrangement was observed in the unchambered long barrows. At Nempnet [Map] and in Wayland's Smithy [Map], the southern end is or was the chambered one; at Charlton Abbot's,a Ablington, and Gatecombe Park, the northern.

Note a. A plan of this barrow, termed Belas or Bellers Knap, will be found in Mem. Anthrop. Soc. i. 474, and in Proc. Soc. Antiq. 2S. iii. 276.

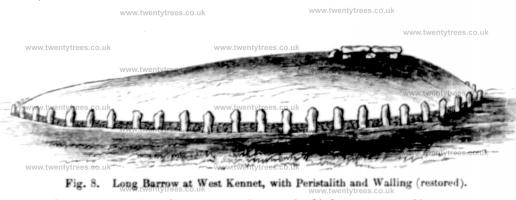

External Basement Walls and Peristaliths.—The lateral ditches, which are so marked a feature in the unchambered long barrows, are for the most part but slightly developed in those which are chambered. In a few, however, they are strongly marked; as in that at Walker Hill; and in some cases where not visible on both sides, are so on the south, as at Littleton Drew and Orchardleich. In the oolitic region, in which these barrows chiefly occur, the superficial strata— whether "corn-brash," "coral-rag," or "Stonesfield slate," afford a building material which the architects of these tombs did not fail to utilize. Nearly all of them are found to have been surrounded by a dwarf dry wall of this material, laid in horizontal courses, neatly faced on the outside, and carried up to a height of two, three, or four feet.1 In this way was produced a supporting wall or podium, which, as has been well observed, in regard to the artistic sepulchres of the Etruscans, "not only defined the limits of the tomb and gave it dignity, but enabled entrances to be made in it, and otherwise converted it from a mere hillock into a monumental structure."2 Such supporting walls were used from an early period, in the construction of the earthen tumuli of the ancient Greeks. Thus of that of Patroclus and Achilles, in the Iliad, it is said,

They marked the boundary of the tomb with stones,

Then filled the inclosure hastily with earth."3

So likewise the tumulus in Arcadia, regarded in Homer's time as that of Æpytus, is described by Pausanias as a mound of earth enclosed at the base by a stone-wall set round in a circle.4 Amongst the less civilized people of Northern Europe, the same mode of constructing barrows obtained; and in Beowulf we are told that the tumulus of the hero of the poem was "surrounded with a wall, in the most honourable manner that wise men could devise it."5

Note 1. At Rodmarton [Map], "a double wall appears to have been erected entirely round the tumulus." (Lysons, Our British Ancestors, p. 138.) It was double also at Ablington, and further researches may show that it was so generally, It is so at least in the chambered cairns of Caithness. Mem. Anthrop. Soc. ii. 242.

Note 2. Fergusson, Architecture, p. 290.

Note 3. Iliad, xxiii. 255. Mr. F. A. Paley ("On Homeric Tumuli," Trans. Camb. Phil. Soc. xi. 2) gives reasons for thinking that the tumulus of Patroclus and Achilles, here described, was not circular, but like our chambered long barrows, and the "ship barrows" of Scandinavia, of elongate form.

Note 4. Iliad, ii. 604. Pausanias, lib. viii. ¢. 16, [Greek Text] Comp. Herod. i. 93.

Note 5. Beowulf, e¢. xliv.

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

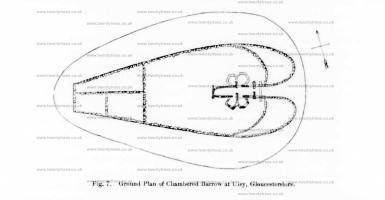

Not only were our chambered barrows surrounded by dry walling, sometimes single, but often double and concentric, but they were often intersected by transverse and longitudinal walls, which seem to have had no particular object, beyond that of giving strength and solidity to the whole; and of forming perhaps temporary causeways, over which those engaged in their construction might convey the stone rubble and earth with which to fill up the entire mound. At Rodmarton and at Ablington, it was noticed that the rubble stone of which the mounds were formed was not thrown together at hap-hazard, but had been piled up more or less regularly. At Ablington, in particular, the layers of loose stones had been placed in a slanting position, and converged towards the centre, in a ridge-like fashion, like the roof of a house; giving to the whole, as seen in section, an almost pyramidal aspect.1 It is of more interest, however, to notice the manner in which the enclosing wall was connected with the entrance to the chambers; in the neighbourhood of which it was usually carried up to a much greater height than elsewhere, and, as at Charlton Abbots, to an elevation even of seven feet. As the lateral walls approach the broad and high end of the tumulus, they turn inwards by a bold but gradual curve; and so finally abut on the two large standing stones, which in the best marked examples of these chambers form the door jambs to the entrance. The gracefully rounded double-convex curve of the walling in this situation has not inaptly been compared to "the top of the figure of the ace of hearts in a pack of cards."2

Note 1. Lysons, Our British Ancestors, pp. 138, 318; also letter to the writer, of July 2, 1864; and see our woodeut on a subsequent page.

Note 2. Lysons, Our British Ancestors, p. 318. In the Caithness chambered cairns the external basement walls form large double concave curves where they abut on the entrances. They have hence been designated "horns." Mem. Anthrop. Soc. ii. 227, 241.

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

On the Chalk Downs of North Wiltshire, where the natural sarsen blocks of which the chambers are formed are common on the surface, the base of the barrow has in several instances been surrounded by a series of such stones placed erect at regular intervals. Natural obelisks of this description formed complete peristaliths to the chambered barrows of Millbarrow, West Kennet, and Wayland's Smithy; as we know from the sketches made by Aubrey late in the seventeenth, and by Stukeley early in the eighteenth century, the accuracy of which is attested by the scanty remains in the two last now alone visible1. It is a curious circumstance that the practice of erecting such stele is referred to by Aristotle, as existing amongst the warlike Iherian people, where he tells us that as many "obelisks were placed around the tomb of the dead warrior as he had slain enemies." I will not insist on this passage as evidence in favour of the Iberian origin of the ancient Britons of the stone period, for this part of our island, though it is not altogether without value in such connection. Continuing the description of the barrows themselves, it must be noted that in two instances, by excavating between the ortholiths or standing stones, at the base of the chambered barrows of North Wiltshire, I have found distinct traces of dry walling, carried up for three or four courses, and formed of "coral-rag," such as is yet used for walls, and which must have been brought a distance of several miles, from the oolitic valleys to the west. This dry walling was no doubt much higher originally, and not less probably than two or three feet in height. Supposing, as seems likely, that the bases of these tombs were originally uncovered by turf or rubble, a peristalith formed by a combination of standing stones and horizontal masonry, similar in its main features to that by which the topes of India are inclosed, must have exhibited a rude elegance, such as we should scarcely have looked for in the age to which these monuments must be assigned.

Note 1. Archeologia, xxxviii. 410, where will be found descriptions of the remains of such peristaliths at West Kennet and Walker Hill. Peristaliths, though rare, occur in the chambered long barrows of Britany, as at Mané-Lud and Kerlescant. In those of Scandinavia they are fuund not only at the base, but likewise high up on the summits of the tumuli, as seen in the ground-plan of that of Hammer, in the island of Zealand. Proce. Soc. Ant. 2nd S. iii. 309

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

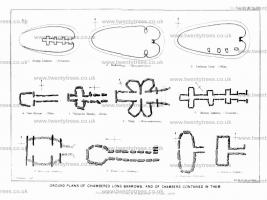

Internal Strueture. The chambered long barrows present three principal types, as regards the plan of their internal construction.

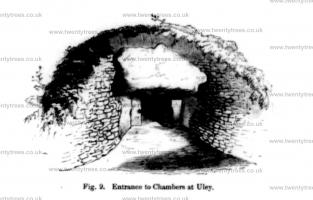

Type I. Chambers Opening into a Central Gallery. (Plate XIV. fig. 1.)—The first in order of importance, and to which the designation of chambered barrow is more especially appropriate, is that furnished with a central avenue or gallery, having a doorway or entrance at one end, by which it was entered, though frequently only in the stooping posture, or even by going on "all fours." This mode of access may indeed be regarded as the essential character of a sepulchral chamber, as distinguished from a vault or cist, of however large proportions, the interior of which ean only be reached, after raising the covering stone, from above. The central avenue or gallery is situate at the broad end of the tumulus,1 and, like the side-chambers often opening out from it, is formed of two rows of stones set on edge, supporting others laid horizontally across, and having the interstices between filled up with horizontal walling, similar to that deseribed as supporting the base of most of these mounds. In the finest examples of chambered barrows, as those of Uley (No. 13), Stoney Littleton (No. 26), and Nempnet [Map] (No. 27), the entrance to the avenue is, or was, by a well-built doorway, formed of two standing and one transverse or horizontal stones, which three stones (trilithon) are, for the most part, of larger and more massive proportions than any of the others entering into the composition of the chambers (see woodcut on the next page). This door-way is found several feet within the skirt or general base-line of the tumulus, and fills up the bottom of the doubly-recurved, heart-shaped dry-walling already deseribed. The entrance, varying from two and a half to four feet in height, was closed by a large stone on the outside; which could be rolled away as required, and was itself covered up with the rubble-stone and earth of which the barrow in general was formed.

Note 1. As a general rule, the narrow ends of the chambered long barrows are entirely devoid of any sepulchral chambers or deposits, for which many, if not most of them have heen searched in vain. In those of Charlton Abbot's and Ablington, however, cists containing skeletons, apparently contemporary with the principal chambers in the former, have been found at the narrow end.

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Archæologia Volume 42 Plate 14. Ground Plans of Chambered Long Barrows and of Chambers contained in them.

1. (Plate XIV. fig. 4).—In the simplest variety of chambered barrows of the first type, as defined above, the gallery leads into a single terminal chamber of quadrangular form, as in that of West Kennet (No. 5). In this instance, the narrow covered passage or gallery (allée courerte) leads from the skirt of the barrow to the entrance to the chamber, formed, like it, of standing and horizontal stones, though of smaller dimensions. This variety of chambered barrow approaches closely to the type of those of Scandinavia, the well-known "gallery tombs," or "giants' chambers."1 In these, however, the chambers are more usually of oblong form, and are placed at right angles with the longer or shorter avenues or galleries of approach, the ground-plan having a general resemblance to the Roman capital letter T. This prevalent configuration has given rise to their designation of half-cross tombs.2 (Plate XIV. figs. 10, 11.)

Note 1. For which, see the works of Worsaae, the late Lord Ellesmere, and the ground-plans by M. Boye, in Sir John Lubbeck's "Pre-Historic Times," p. 105, in Proc. Soc. Ant. 2 8, iii. 309; and lastly those in Nilsson's Primitive Inhabitants of Scandinavia— Stone Age, by Sir J. Lubbock, p. 124, pl. xiv. figs. 243245. For views of gallery and chambers at West Kennet, see Archæologia, xxxviii. 411.

Note 2. Both oval and circular chambers do, however, occur, but in all the approach is by a longer or shorter passage or gallery. Hence their Swedish name of Gongegrifter, passage or gallery tombs. Nilsson, 1. c. i417.

2. (Plate XIV. fig. 5.)—In the second variety of the first type, of which Wayland's Smithy is a good example, in addition to a small terminal chamber, there are two lateral chambers facing one another, one on each side of the central gallery, in the form of a Latin cross, so as to present an arrangement like that of transepts in a church.