Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Text this colour are links that are disabled for Guests.

Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page. Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

Archaeologia Volume 62 1910 Pages 333-352 Part II is in Archaeologia Volume 62 1910 Pages 333-352.

The Development of Neolithic Pottery.

The outstanding feature of Mr. Abbott's discoveries at Peterborough is the occurrence in close association of two classes of pottery that can be clearly distinguished. The rounded base has long been regarded as a leading characteristic of neolithic pottery in Scotland, and the exploration of cairns in Arran by Dr. Thos. Bryce1 leaves little doubt on the subject. But perhaps the closest parallel in that area to the particular form under discussion was found in the north chamber of a cairn at Achnacree, Argyleshire,2 without any other indications of a burial. In the south chamber was found a somewhat similar bowl, with cylindrical body and rounded base, recalling the profile of an Irish specimen in the British Museum (pl. XXXIX, fig. 1). An attempt will be made in what follows to show that this similarity is not accidental; and it is the Peterborough find, in conjunction with certain isolated discoveries, that suggests an origin for the large class of Bronze Age sepulchral pottery known as "food-vessels".

Note 1. Proc. Soc. Ant. Scot., xxxvi. 135, with figs.; see also Journal of Anthropological Institute, 1902, new ser. v. 398

Note 2. Proc. Soc. Ant. Scot., ix. 414, pl. xxiv. fig. 2 (7x4 in). The other type (fig. 1) resembles one from Bute figured in vol. xxxviii. 48, fig. 20 (diam. 5 in.). Cf. Anderson, Scotland in Pagan Times: Bronze and Stone Ages, 271.

It is important to add that on the same site and beneath the same calcareous seam was found a large and practically complete specimen, 96 in. high, of a well-known drinking-cup type (pl XXXVII, fig. 2),called α by Mr. Abercromby, and another of his type β, 5.3 in. high, covered with horizontal cord-markings. The association is rendered practically certain and all the more important by the discovery of type α and neolithic ware in considerable quantity in the Peterborough pits. Though on both sites there may have been some interval of time between the two classes of ware, it is now clear that they were made and used by dwellers on the same spot, living apparently under the same conditions; and an explanation of the presence of two distinct but practically contemporaneous types in the same area now seems to be possible. It is first, however, necessary to bring together examples of the thick and coarse blackish ware that can be safely classed with the Mortlake bowl and the lower finds in the pits at Peterborough.

The accompanying illustrations of two perfect specimens brought up in a net from the Thames at Mongewell, near Wallingford (pl. XXXVIII, figs. 2, 3), are from photographs kindly supplied by Mr. G. W. Smith, who has the originals in his collection and states that one is 42 in. high and 6 in. in diameter, the other 3½ in. high and 5 in. in diameter. Four specimens therefore, at least, are known from the Thames; and there is sufficient evidence to prove that the type is not confined to the South of England.

Our Fellow Mr. John Ward found in Rains Cave, Longcliffe, Derbyshire,1 enough of a round-bottomed bowl to determine its original appearance and dimensions, and gives the following description: "Diameter about 8½ in.; paste coarse and reddish, hand-made, variable in thickness, but generally thicker at the bottom than elsewhere. From the obvious discoloration of the lower parts externally and traces of smoke, we may safely conclude that it was used as a stew-pot. The shape is admirably adapted for this purpose. When placed in the embers of a fire its rounded shape would prevent fracture, and in this respect it is an anticipation of the flasks and dishes of the chemists. The paste of these hand-made vessels was mixed with crushed calc-spar, which is common in the district and scarce elsewhere; from which we may infer that they were made in the locality." The illustration shows the rim alone ornamented, and on the same plate, fig. 4, is a fragment of a vessel with parallel cord pattern, the paste being thick and blackish. As an indication of date it may be mentioned that wheelmade pottery and iron were found in this cave, but no bronze, which is all in favour of the rougher pottery being neolithic.

Note 1. Journal of Derbyshire Arch. and Nat. Hist. Soc., xi, (1889), 39, pl. ii. fig. 3. The height would be about 6in.

An interesting find very much to the point is due to Mr. J. R. Mortimer,1 who for nearly half a century has been excavating in the East Riding of Yorkshire. Under one end of a true long barrow at Hanging Grimston was found a subterranean dwelling that had evidently been destroyed by fire; also four shallow round-bottomed vessels of plain ware with diameters of 12 to 13 in. and depths varying from 3¾ to 6in. The shapes are not identical with the type under discussion; but the discovery of four domestic specimens, evidently earlier than a long barrow that was not wholly explored but probably contained burials, is certainly instructive. In the same Riding, Dr. Greenwell (age 89)2 has found roundbottomed bowls very similar to those from Scotland, but not decorated and of palish brown clay, anything but heavy. He also mentions the occurrence of dark-coloured plain pottery, presumably the remains of domestic vessels, as common in the Wold barrows. These are, however, so fragmentary that no reconstruction has been possible, though from the curvature Dr. Greenwell concludes that many of the vessels were round-bottomed.

Note 1. Forty Years' Researches, 103, pl. xxxi. fig. 248.

Note 2. British Barrows, 143, fig. gt on p. 107.

A curious pottery vessel referable to the same period was found by Bateman in an interesting barrow opened in 1843 near the village of Biggin, Derbyshire. The find has since been published in another connexion by Hon. John Abercromby,1 but the original illustration2 gives a better idea of the vessel than the recent photograph. It was found on a small heap of neolithic flint implements in association with a human skeleton, the knees drawn up and the skull having an index of 74.3 (dolichocephalic). The cylindrical neck broadens out below to a projecting fillet, beneath which is a hollow moulding and a hemispherical body. The ornamentation consists of bands of short incised lines and herring-bone pattern, the whole being 4 in. high and 2½ in. in diameter at the widest part. Bateman commented on its novel and unprecedented shape, and drew particular attention to the absence of metal here in any form.

Note 1. Man, 1906, no.-44, fig. 5.

Note 2. Thomas Bateman, Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire, 43. Most of the find is now in the Sheffield Museum.

The late Gen. Pitt-Rivers had a shrewd suspicion that much of his no. 1 quality British pottery was neolithic. Wor barrow, which he definitely assigned to the long-barrow period, produced a number of long skulls, and some pottery fragments1 that evidently belonged to round-bottomed bowls exactly corresponding to that from Mortlake (pl. XX XVII, fig. 3). More came from barrows at Handley in the same neighbourhood, and his comments on the ware should be read in this connexion.

Note 1. Excavations in Cranborne Chase, iv. 67, pl. 261, fig. 17; see also fig. 10, and pl. 246, figs. 2-7; pl. 298, fig. 8; pl. 304, fig. 7; remarks on p. 163.

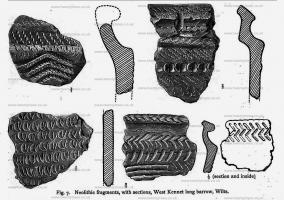

The most significant find of this class of pottery in England was published by this Society in 1860, with copious illustrations.1 Under the auspices of the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Dr. Thurnam opened a chambered long barrow at West Kennet, near Avebury, and found skeletons with elongated skulls, flint implements, and three heaps of pottery, specimens of which are now in the British Museum, and include four rim fragments of different vessels with the characteristic hollow moulding below the lip, of thick ware ornamented in the usual way with the finger-nail, impressed cord, pointed stick, etc. (fig. 7). Two fragments figured by Thurnam1 are quite distinct from the rest, of black and brown colour, and obviously of later dates. One is part of a black pottery dish with several round holes in a flat base, the original dimensions being 5½ in. diameter at the mouth, and 4 in. at the base, the wall being 2 in. high. A complete specimen in the British Museum from Chatillon, Switzerland (doubtless from a Bronze Age lake-dwelling), has nearly vertical sides, but dimensions in the same proportion: 7¾ in. at the mouth, and 2¼; in. high. These vessels were probably used like the modern colander, but the original form of the second exceptional fragment cannot be determined, though the incised lattice pattern of double lines on a burnished black surface points to the Early Iron Age or the Roman period.

Note 1. Archaeologia, XXXVIII. 405.

Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1930 V45 Pages 300-335. While there seems to have been among the West Kennet pottery a considerable variety of vessels, the most characteristic and best known form is that of a highly-ornamented round-bottom bowl with spreading lip and contracted below the rim. These are well represented by bowls in the British Museum, found in the Thames at Mortlake and Mongewell.1 The ware is coarse and imperfectly fired, even when the surface is burnt red, usually showing a black core; the paste is often mixed with broken shells or particles of flint or other stone, and. The ornamentation shows great variety, some of it being produced by impressions on the soft clay of twisted cord or sinews, finger tips or finger nails, and very frequently of the articulating ends of bones of small birds and mammals2. Some of the fragments from the Sanctuary seem to have belonged to bowls of this type and are illustrated on Plates VII., VIII.

The fragments of beaker (except No. 2) are not illustrated, as the type is so well known, the ornament consisting exclusively of rows of horizontal parallel lines executed in the characteristic notched manner.

Note 1. Archæologia, lxii., 340.

Note 2. New light on an old Problem, Antiquity, September 1929, 283—291