Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Text this colour are links that are disabled for Guests.

Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page. Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Walter of Guisborough, a canon regular of the Augustinian Guisborough Priory, Yorkshire, formerly known as The Chronicle of Walter of Hemingburgh, describes the period from 1066 to 1346. Before 1274 the Chronicle is based on other works. Thereafter, the Chronicle is original, and a remarkable source for the events of the time. This book provides a translation of the Chronicle from that date. The Latin source for our translation is the 1849 work edited by Hans Claude Hamilton. Hamilton, in his preface, says: "In the present work we behold perhaps one of the finest samples of our early chronicles, both as regards the value of the events recorded, and the correctness with which they are detailed; Nor will the pleasing style of composition be lightly passed over by those capable of seeing reflected from it the tokens of a vigorous and cultivated mind, and a favourable specimen of the learning and taste of the age in which it was framed." Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

CWAAS Transactions 1891 Volume 11 Article 16 is in CWAAS Transactions 1891 Volume 11.

1891. Art. 16. — Mayburgh [Map] and King Arthur's Round Table. By C. W. Dymond, F.S.A.

The accompanying plans and sections of these ancient remains are reduced photo-lithographed copies of originals drawn to one scale from exact instrumental surveys made in October, 1889. The objects thus de lineated, though not the only relics of remote ages in their district, are by far the most prominent among them. Both are on the south side of the river Eamont, close to the village of Eamont1 Bridge, and near together;—their centres being but 445 yards2 apart.

Southward from the Round Table, centrally distant from it about 225 yards, and with little more than the width of a road between it and the river Lowther, there formerly existed a slight annular embankment, known as the "Little Round Table," vestiges of which were visible until about the year 1878, when, according to Mr. William Atkinson, the last traces were obliterated in widening the approaches to the new lodge-gates of Lowther park. He describes what he saw as consisting of "a low circular ridge.... not more than 6 to 9 inches above the level of the surrounding ground, and from 3 to 5 feet broad at the base."3 There is some difference of state ment between authorities who give the diameter of this ring. Stukeley, partial to round numbers, calls it 100 yards, and says, "the vallum is small, and the ditch whence it was taken is outermost."4 Hutchinson, who wrongly locates it "nearer to Emont Bridge," (Lowther bridge?) describes it as a "circular ditch, with a very low rampart,.... without any apertures or advances;"5 and puts the diameter at 70 paces. It is clearly shown on a well-engraved plan in Pennant's First Tour in Scotland, 1769, herewith reproduced in facsimile on a rather smaller scale. The outer diameter measures 80 yards, after making a needful adjustment of the slightly erroneous scale attached to the plan. No ditch is shown,—the size is too small for that,—but there appears to have been an entrance, or at least a gap, through the bank, a little east of the north point, not quite in the direction of the Round Table, which is somewhat west of north. Mr. Atkinson does not mention the ditch, which may have disappeared. He estimated the diameter of the ring at from 60 to 80 yards. On a comparison of the data, we may probably assume that the latter figure is very near the truth. The authors of Beauties of England and Wales, after referring to the Round Table, somewhat obscurely describe this inclosure as follows:—"On the adjoining plain are a larger ring with low ramparts, and some smaller ones, [rings?] at present [1814] scarcely visible."6

Note 1. Locally pronounced "Yammon:" whence, perhaps, Yeoman's bridge, an old form of the name.

Note 2. Measured on the 25-inch ordnance map, which, however, is not always quite trustworthy as to the smaller dimensions and distances.

Note 3. Trans. Cumbd. and Westm. Ant. Soc., vol. VI, P. 444.

Note 4. Itinerarium Curiosum, Cent. II, P. 43.

Note 5. Excursion to the Lakes, 1773-1774, p. 91.

Note 6. Westmorland vol, p. 111.

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

1769. Plan of 1. Mayburgh Henge [Map], 2. King Arthur's Round Table and 3. Little Round Table and

A field, until lately fenced off, on the south-east side of Mayburgh, and covering the space between it and the main and occupation roads, for no good reason that I can find, was called "High Round Table." Perhaps a curved escarpment, the western and straighter part of which is shown in the plan of Mayburgh, together with other wavy scorings of the surface, may have conjured up in some imaginative mind the idea of another artificial work like the Round Table. It is hardly likely that the name had any reference to the adjoining Mayburgh, which is self inclosed.

A large cairn once crowned the high northern bank of the Eamont, nearly opposite to Mayburgh. It was being removed even in Stukeley's time; and, apparently, has long since utterly disappeared, unfortunately without any note having been taken of its contents. He describes it as "a very fine round tumulus, of a large size, and set about with a circle of stones: " from which simple record he characteristically jumps to the conclusion that " this in all probability was the funeral monument of the king that founded " Mayburgh and the Round Table.1 That this cairn was cöeval with Mayburgh is, however, not unlikely, if any weight is to be attached to the fact that both were built with similar materials: for Hutchinson states that it "appears where the turf is broken, to be composed of pebbles; it is surrounded at the foot with a circle of large stones, of irregular forms, sizes, and distances, of the cir cumference of eighty paces."2

Note 1. Itin. Curios., II, 44..

Note 2. Exc. to the Lakes, 98.

A mile-and-a-half due south from Mayburgh, near the top of a hill of moderate height, are the remains of an intrenched upland settlement known by the name of "Castlesteads;" and, three-quarters of a mile east of this, on the other side of the Lowther, half-a-mile south of the village of Clifton, are two standing-stones, of no great size or interest,—perhaps the only relics of a once-important megalithic work. Stukeley mentions other tumuli and megalithic groups in the Clifton district;—all of which, probably, have long since disappeared.

As to local ancient roads, I have not had an opportunity of gleaning much information; and therefore touch upon the subject with diffidence and reserve. One known Roman way—High Street—either traversed or skirted the locus in quo. Leading from Ambleside over the highest intervening mountain-ridges, it passed through Tirril to Yanwath; beyond which there appears to be some differ ence of opinion as to its course. In an archæological map in Lapidarium Septentrionale, 1875, published by the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle-on-Tyne, and embodying the results of the best and most recent research, this part of the road is laid down as taking a north-easterly direction from Yanwath, and terminating at Brougham, a full mile east of Eamont Bridge. There it would unite with one of the great roads—that passing near Appleby and Kirkby 'Tore, —just south of the point where it crossed the Eamont on the way to Penrith and Carlisle. Although much of High Street on mountain and moor may still be seen, and is accurately laid down in the ordnance maps, its whole course is uniformly dotted in the archaeological map as "not surveyed, but in accordance with the best local authorities." It is, therefore, not clear what degree of trust may be placed in those portions of the indicated line which are undefined on the ground; and I am not aware that any part of the ancient road, or a branch of it, has actually been traced between Yanwath and Brougham. If now we turn to the large scale ordnance maps, we get a different testimony. In them, High Street is made to diverge from the present Tirril—Yanwath road one-third of a mile short of the bridge over the railway, and to strike the river a few yards to the west of Yanwath Hall, where there would be a ford or a bridge It may be of some importance, in connexion with the subject of this paper, to settle such points as this: and it is evident we need more information about the history of the local roads, many of which are full of hints of survivals from Roman times. Pennant's plan does not help us; there being no indication thereon of an east and west track. The present road was, I believe, made about a century ago; and, from Stukeley's statement that " one end [of the Round Table —doubtless he means the northern end] is inclosed into a neighbouring pasture," it may be inferred that the line of the Roman way at that part, unless lost beneath the sod, did not coincide with the present one. One thing is sure, —that, if it came in this direction, it must have passed either to the north or to the south of the escarpment ex tending from the Round Table about 400 yards southward. Bishop Gibson, in his "Additions" to Camden, (ed. 1695, p. 815) makes the Roman way between Brougham and Penrith, after reaching the former place, lead " directly to Lowther-bridge, and so over Emot into Cumberland."

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Site and general description.—Mayburgh [Map],1 seated on a wide low mound of glacial drift, consists of a rude circular cincture of small stones inclosing a nearly level grassy area, except on the east side, where an entrance interrupts the continuity of the rampart. In the midst—though not quite in the centre of the inclosure—stands a massive monolith, the only remaining member of a group, or groups, which once formed a prominent feature of the whole work.

Note 1. Pronounced, and often written, Mayborough.

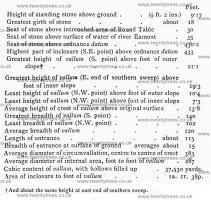

Dimensions.—The following list will be found to include all the important dimensions. In so far as the reference is to that which can be accurately ascertained, and to the present state of the work, the figures may be taken as trustworthy. It is, however, impossible to say how much the vallum may have suffered from dilapidation, or to what extent this may, here and there, have altered its form.—

Note 1. And about the same height at east end of southern sweep.

The vallum.—Hutchinson greatly under-estimated the breadth of the vallum, "near 20 paces "---say 50 feet. It consists of stones evidently brought either entirely from the bed of the Eamont, distant 300 yards, or partly from thence, and partly from the Lowther, distant 540 yards1. For the most part they are of very small size,—not much bigger than a man's fist;—though boulders, 18 inches in length, with a very few as much as 30 inches, may, here and there, be seen. Save in scattered patches, the sur face of the stone bank, which at first was probably left bare, has become clothed with a thin coating of soil, now grassed over. In this unpromising belt, a number of trees, chiefly ash, have taken root; their umbrage contributing to deepen the retirement within. From Hutchinson's account, we learn that the surrounding land, now almost completely cleared, was, in his day, "on every side grown with oaks and ashes,"2 possibly the descendants of the trees of ancient woods, in the depths of which this rude hypæthral chamber was secluded.

Note 1. The opinion of Mr. Goodchild, of H.M. Geological Survey, as reported by Mr. Atkinson, (see vol. VI, p. 451 of these Transactions) is that "Maybrough may very well have been originally one of those great mounds of glacial drift. and that the centre has been cleared out, and the larger stones thus obtained placed round the margin, while the gravel and smaller stones were used to form the level internal area. The large stone in the centre is one of the great bluish-grey boulders of volcanic ash, so commonly found scattered over the country by glacial action, and probably brought from the Lake District, and it would, with the others formerly existing here, in all probability be found in the centre of such a mound." That the standing stone was an erratic block, is most likely: but the rest of the theory does not altogether commend itself to our acceptance. It would be singular if this were the only ridge, out of many in the neighborhood, on which such an accumulation of stones gathered: and the theory does not seem consistent with the contours of the surface and the nature of the ground,—evidently, as the sections show, the natural top of the swell, ap parently nearly, if not quite, free from stones.

Note 2. Exc. to the Lakes, 92.

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

The area.—The inclosed area, with an average diameter of 287 ft., may originally have been a little larger; for it is likely that, in course of time, some of the loose materials of the bank, disturbed by growth of trees and other agencies, may have slid downward and encroached upon it. Stukeley calls the diameter 300 ft., and says that, at the time of his visit [See Stukeley], (15th Aug. 1725), the land was ploughed up and growing corn. Pennant estimated the diameter at 88 yards; which is a few feet less than the width at the narrowest part: for the field, as the plan shows, is not quite round. Hutchinson describes it as "a fine plain of meadow ground, exactly circular, one hundred paces [250 ft.] diameter1."

Note 1. Exc. to the Lakes, 93.

All About History Books

The Deeds of King Henry V, or in Latin Henrici Quinti, Angliæ Regis, Gesta, is a first-hand account of the Agincourt Campaign, and subsequent events to his death in 1422. The author of the first part was a Chaplain in King Henry's retinue who was present from King Henry's departure at Southampton in 1415, at the siege of Harfleur, the battle of Agincourt, and the celebrations on King Henry's return to London. The second part, by another writer, relates the events that took place including the negotiations at Troye, Henry's marriage and his death in 1422.

Available at Amazon as eBook or Paperback.

The megaliths.—The standing stone is 31 ft. 6 ins., N.W. by W., from the centre of the plot; a distance which lends support to Stukeley's theory of an inner circle; and agrees tolerably with his estimate that "this inner circle was fifty foot in diameter."1 He proceeds to state his conviction that there "have been two circles of huge stones; four remaining of the inner circle till a year or two ago, [about 1723], that they were blown to pieces with gun powder:... one now stands, ten foot high, seven teen in circumference, of a good shapely kind; another lies along.... One stone, at least, of the outer circle remains, by the edge of the corn; and some more lie at the entrance within side, others without, and fragments all about."1 So much for Stukeley's fairly trustworthy record of facts. Pennant comes next, in 1769, 44 years later. According to his measurements, the height and girth of the stone were 9 ft. 8 ins. and 17 ft. respectively. He says, "there had been three more placed so as to form (with the other) a square. Four again stood on the sides of the entrance, viz. one on each exterior corner; and one on each interior; but, excepting that at present remaining, all the others have long since been blasted to clear the ground."2 Writing of the standing stone, about four years after Pennant, Hutchinson, who classes it as "a species of the free stone," gives the height as "eleven feet and upwards," and the "circumference near its middle twenty-two feet and some inches;" and tells us, "the inhabitants in the neighbourhood say, that within the memory of man, two other stones of similar nature, and placed in a kind of angular figure with the stone now remaining, were to be seen there, but as they were hurtful to the ground, were destroyed and removed."3 West makes the curious mistake of calling the monolith "a red stone."4 Pennant's plan, upon which are marked the places of seven of the missing stones, shows the one re maining, with the seats of three others,forming a rectangle, 60 ft. by 53 ft., oùt of square with the cardinal points; also the seats of two other stones, 40 ft. apart, and not quite vis-à-vis, at the inner corners of the entrance; and of two more, 45 ft. apart, one on each side, at about the middle of its length. Little trust should, however, be placed on the accuracy of this evidence; for we are not told that the seats of the missing stones were then to be seen: and perhaps we may be justified in concluding that there is not sufficient reason for regarding this apparent rectangular arrangement as other than accidental. We may even go farther, and assume, with Stukeley, that a stone circle 50 ft. or 60 ft. in diameter once surrounded the central part of the ground; also that the avenue of approach was flanked by at least two great stones on each side. It is to be wished that we had stronger evidence as to the larger concentric circle imagined by Stukeley, who appears to have seen only one stone "by the edge of the corn." That such circle did once exist, is far from im probable: for in Mayburgh there is much that recalls the plan of Avebury, which exhibits a similar association and ar rangement of stones and embankment. As to the weight of the remaining stone, estimates have differed considerably. It is not known exactly how deeply it is sunk into the ground. One Abraham Rawlinson, 83 years of age, told me that, with a tourist from London, he once dug down more than four feet by the side of the stone without reaching the bottom. It was found to taper downward, as though to a small extremity. A large piece was hammered off and weighed; and from this specimen the weight of the whole stone was calculated to be 15 tons. Others have put it at 20 tons. From my own measurements, I think the content may be from 155 to 160 cubic feet, and the weight 11 or 12 tons.

Note 1. Itin. Curios., II, 44.

Note 2. First Tour in Scotland, p. 257.

Note 3. Exc. to the Lakes, 93.

Note 4. Guide to the Lakes, 7th ed., p. 167.

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Camden says that Penrith castle, in the reign of Henry VI, was repaired out of the ruins of Mayburgh. Bishop Gibson, one of his editors, denies this. The statement is repeated by Nicolson and Burn, who also print a record that "in the reign of Hen. 6 there seems to have been a general contribution towards the building, or perhaps rather rebuilding of Eamont bridge,"1 for which an in dulgence was granted by bishop Langley. It is not un likely that, for this purpose, Mayburgh may have been despoiled of most of its megaliths; and that the other less probable assertion may have so originated. The authors of Beauties of England and Wales2 are yet wider of the mark when they make the last-named writers say that it was Kendal castle which was thus repaired:—an evident misprint.

Note 1. Hist. and Ant. of Westnt. and Cumbd., I, 413.

Note 2. Westmorland vol. p. 113.

Site.—The site of the Round Table has been aptly described by Stukeley [see Stukeley] as "a delicate little plain, of an oblong form, bounded on 'one' side by a natural de clivity." On the other side flows the Lowther. The ground thus shut in is about 300 yards in length, and has an average breadth of 130 yards. The Round Table is at its northern outlet, where it suddenly expands, continuing on the same level to the banks of the two rivers. In the opposite direction, the surface begins gradually to rise at the distance of 230 yards from the Round Table.

Description.—This earthwork has been formed by digging a ditch nearly around an oval area; with the excavated material forming an inclosing embankment, with a berm between it and the ditch, and raising a slight and nearly circular platform eccentrically in the inclosure. Originally, the continuity of the ditch was broken at two opposite points by leaving gangways to give access to the interior of the work; in line with which were two passages through the embankment. The northern of these two entrances was all but completely destroyed in making the Yanwath road, about the end of last century; only a portion of its inner end being left visible at the field-gate. A slice was also cut off from the eastern side of the embankment by straightening and widening the Clifton road, which appears to have been done at the same time. The inner area around the platform is nearly level; but the berm rises from the edge of the ditch to the foot of the bank. The section G—H shows what must have been the original form and height of the latter, which, in most other parts, has been much degraded. Especially is this so along the south-western side, where the bank has been scooped out and flattened almost beyond recognition. As to the material of which it is made, Stukeley says,—"the composition of it is intirely coggles and gravel, dug out of the ditch; adding that "the inhabitants carry it away to mend the highways withal."1 Perhaps this may account for the deformation. There is, however, nothing visible to indi cate this alleged stony nature of the ground; for the whole is carpeted with fine turf constantly grazed; and not a stone can be seen on the surface. Such is the irregularity of the work on the plan, that it evidently could not have been set out even by pacing,—still less with a measuring line from a centre. I learned from the old man before mentioned that more than 6o years ago, to the best of his poor recollection, the then owner of the "Crown" inn, one Bushby,—either the same who built it in 1770, or his son,—deepened the ditch, and threw the earth on the banks. I do not, however, imagine that much in this way was done;—probably not enough to alter to any appre ciable extent the features of the work.

Note 1. Itin. Curios., II, 43.

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.