Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page. Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

Collections Historical and Archaeological MontgomeryshireVolume 35 1908 is in Collections Historical and Archaeological Montgomeryshire.

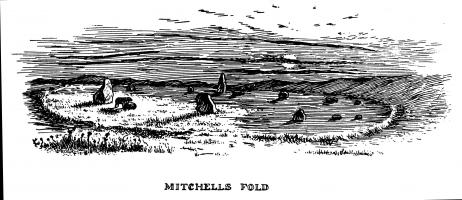

The principal prehistoric remain in the parish is one of the three monuments, which lie on the side of Corndon, and are known as Mitchell's Fold [Map]. There is a full description of these monuments in the Rev. Charles Henry Hartshorne's Salopia Antiqua, which the writer herewith quotes in full:

(Page 30). Immediately at the south eastern foot of Corndon are three remarkable monuments at no great distance asunder, whose erection must be ascribed to the most remote antiquity. Two of these are in our own county2, the slight remains of the third, a few paces out of it, and consequently stands in Montgomeryshire. In the relative positions of these monuments to each other there is something very singular, and it would lead an imaginative person to consider them Draconite.

Note 2. Shropshire.

If we take the remains near the Marsh Pool first, which have erroneously obtained the designation of Hoar Stones, but which for the sake of correctness, I shall discontinue and call the Marsh Pool Circle. If we begin here at the north-west. and go over Stapeley Hill, through Mitchell's Fold, and thence descend to the Whetstones [Map], which lie at the base of the mountain before-mentioned, we shall have proceded in a curved or sinuous line for a distance of two miles. In our course we have the three monuments in question: at one extremity a circle consisting of 32 upright stones ranged round its circumference; at the other extremity the mutilated fragments called the Whetstones [Map], and upon the intervening elevated ground, the larger works of Mitchell's Fold [Map], which are rather more than midway along the curve. Now in these there is a degree (p. 31) ot resemblance to what exists at Stanton Drew and Avebury [Map]. At the latter place, in fact, the curvature of the avenue of approach to the great temple is precisely similar, whilst the two circles there are surrounded, as is this, with a vallum of earth, having its fosse within. It is true that here we no longer see the stones on each side forming an avenue of communication with the Body of the Serpent, or the two temples upon the high ground, but knowing the tendency of stone to become obliterated by moss, to sink into the soil, or their chances of destruction from the wicked spirit which has always prevailed among ignorant cultivators of the land, who look upon them with no higher feelings than utility would inspire, and who recklessly make them subservient to the purposes of building some miserable dwelling, we shall not be at a loss in accounting for their deficiency. Whether this was ever when in its most complete state an ophite hierogram, must continue unknown to ourselves and succeeding ages. That it was designed with a religious intention will not admit of a doubt, though the precise nature of the solemnities, and the objects of adoration the worshippers had before them must still remain veiled in perpetual darkness. We know that the hierogram of the Sun was a circle; the temples of the Sun were circular. The Arkites adored the personified Ark of Noah; their temples were built in the form of a Ship. The Ophites adore a Serpent; their temples assume the form of the Serpent. And to come more home to our own times and feelings, the Christain retains a remnant of the same ideas when he builds his Churches in the form of the Cross, the Cross being at once the symbol of his creed and the hierogram of his God.1

Note 1. Observations on Dracontia, by the Rev. John Bathurst Deane. Archaol., Vol. xxv., p. 191.

![]() Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

(Page 32). That the monuments upon Stapeley Hill were devoted to the Serpent worship is an idea that must rest purely upon conjecture. And after the most diligent sifting and careful consideration of this question, we are in the possession of little beyond it to offer. To a certain degree these remains are conformable to those temples which Stukeley a century ago, and Mr. Deane at the present day, have with much erudition and ingenuity pronounced to be of Dracontian nature. Yet, admitting this to be of such kind, we are still unable to fill up the Serpent's form entirely. We have only remaining its Head, the Whetstones, its Tail, the Marsh Pool Circle; and a portion of its Body, Mitchell's Fold, to supply the hierogram; the Vertebrae or Avenue is wanting.

(Page 33). The Whetstones [Map], or head of this presumed Ophital Toor (for I need scarcely say that I can only regard such theories in the light of agreeable fancies), lie at the foot of Corndon upon the Shropshire side. They are so close upon the borders of this county as to be almost in it. These three stones were formerly placed upright, though they now lean, owing to the soft and boggy nature of the soil. They stand equi-distant, and assume a circular position. Originally they evidently formed part of a circle, for they stood too far apart to have ever been supporters of a Cromlech, even if their actual bearing with regard to each other did not forbid the supposition. The highest of these is four feet above the surface; one foot six inches in thickness, and three feet in width. Vulgar tradition has given them their present title, though without any apparent reason, for as they are all of Basalt, they would be ill adapted to the use which the common acceptance of their name implies. Can this title refer to anything sacrificial? and be derived from the C. Brit. "gwaed-vaen," or bloodstone? It is all supposition, and the utmost insight we can obtain is slight and insignificant. Our facts are so few, that we are compelled to draw upon the imagination, which though it be the most captivating, is in proportion the most unsafe antiquarian guide. Let us see, however, how far etymology will serve us in (p. 34) throwing light upon the objects of our enquiry, that is upon these and such as are in their immediate vicinity ....

As for Mitchell's Fold two surmises may be offered. The first would dissolve the word into the A.S. Middel-Fold "quasi" Mitchel-Fold, or the fold lying betwixt the Whetstones and Marsh Pool Circle; the other would connect it with the Camden's British, "mid," an enclosure. Corndon, in Camden's Britannia, simply signifies a dark horn or projection; in Celtic, it signifies the crowned mountain: from "Coron," a crown, and "don," a mountain; or "Corn," from Carn, a heap of stones, and "Don," on high: alluding to the six Carnedds on its summit. The name of "Dysgwylfa" underneath it denotes a look-out place.

(Page 35). At the present day Mitchell's Fold consists of fourteen stones; ten of which are more or less upright, and four of them lying flat. They are disposed at irregular distances in an irregular ciicle, which is ninety feet from North to South, and eighty-five from East to West. When the brief description of it was written, that is found in the Addenda to Camden's Britannia1 none of the stones were prostrate. One at the eastern point only is mentioned as inclining; since that period it has fallen. Though there be two or three accidental omissions of distance between some of the stones, the following measures may be received on the whole as conveying an adequate notion of their relative positions. If we allow three feet for the average width of each stone at its base, and place them according to the intervening distance between the eleventh and twelfth, five feet apart, it will make the complete circle consist ot thirty stones, and there was formally an entrance on the eastern side, where the stone of greatest altitude now remains.2 The adjacent one on the western side, now flat (p- 36) was leaning when Gough received his account of it, but when Mr. Ducarel's informant saw it, the two served as sides to the Portral of entrance, and even had one lying accross the top. These losses, and most likely more important ones unrecorded, have happened to Mitchell's Fold within the last eighty-six years, when the spot was first described.

Note 1. This account is as follows:— "The greatest diameter is ninety-one feet and-a-half." (These measures must have been taken from exterior to exterior. Mine, which were carefully taken with a hundred foot tape, with the aid of an assistant, vary a little from these dimensions.) "There are fourteen stones remaining, and the vacancies required thirteen or fourteen more, a is six feet high; o is as high, but leans. These two stones are six feet distant." (These refer to the eighth and ninth stones in my plan). "The next in size is." (This is the fourth stone in my plan), "from whence is a prospect westward between two sloping hills to the cultivated part of the Long Mountains, which prospect would have teen lost in any other situation of the circle." "y is a stone eighty yards distant." (See this marked in the plan of the second circle). "This way is high land of Corn Alton Forest."—Camden's Britannia, p. 534. Unfortunately the Editor does not say when or from whom he received this communication. The legend on the spot was the same then as it is at present.

Note 2. In a letter from James Ducarel, Ksq., to his brother. dated Shrewsbury, May 11, 1752, and published in Nichol's Literary Anecdotes, I find the first mention of these antiquities. He says, "One Mr. Whitfield, an eminent surgeon and a good scholar who is a man of good fortune in this town, has told me that he had given a friend of his a rough draft that he himself took of the Medgley's Fold above two years ago. As he came home one night he fell in amongst the stones by chance, and thinking it a Druid temple returned there next day to view it, when he was confirmed in his opinion; and took the above draft, which he gave to a friend to do out neatly. He has promised me a copy of it, if his friend, who is a lawyer, has not thrown it away. I told you in a former letter that Rynaston (Kynaston) and I are to take a ride to see it when he has a little leisure, as we must lie out when we go." — Literary Anecdotes, Vol. iv. p- 621.—Again in June, of the same year, he says, "We shall go to Medgley's Fold shorty. Whitfield says your upright is pretty true. What you call a Portal, he calls a Tribunal, says there was a stone across your two Portals, like those of Stone Henge, and that the stone at eighty yards distance was an altar. Some of the little stones nn the east are almost over-grown with moss and grass "—I.B., p. 623.

![]() Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

The decay seems to have been gradual, and we are happily spared the pain of noticing that it has suffered through ignorant and wilful despoilers. A valum originally enclosed the whole, evident marks of which may be seen on the north western side.

If we commence on the western side of the clircle, the existing portions of it appear as follows:—

No. 1 is three feet high, and fourwide: distant trom the second twenty-one feet.

No. 2 is five feet high: distant from 3rd forty feet.

No. 3 is leaning, but still:hree feet above surface and ten feet from fourth.

No. 4 is flat.

No. 5 is flat.

No 6. is four feet above surface.

No. 7 is much depressed: nine feet from 8th.

No 8 is five feet ten inches high, which formed (p. 37) the northern side of the Portal, is foursided, measures two feet two inches on two sides, eight inches and one foot seven inches on other two sides..It is six feet from 9th.

No. 9 on the other side of the Portal is prostrate, and is thirty feet from tenth.

No. 10 is two feet above surface, and is thirty four feet from eleventh.

No. 11 is two feet above surface: is five feet from 12th.

No. 12 is one foot high.

No. 13 is large and prostrate: there are marks of one having stood between the 13th and 14th stone: from 13th stone to 14th is twelve feet.

No. 14 is two feet above ground, and fifteen feet from the first stone.

![]() Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

There is a second circle a little elevated, and having its centre highest, about seventy paces to the south east of the great one. This measures seventy-two feet from north to south, and has seven stones that vary from two feet to one foot in height and are four feet asunder, which distances make it to contain thirty stones like the other. On the eastern verge of this circle is a very large stone two feet above the surface. This must be that figured in the Addenda of Camden, I imagine. Faint indications appear of a third Circle to the north east of this, but the marks are so slight that nothing satisfactory can be made out. The whole of this ground is traversed in several places by mounds, which have every appearance of having been constructed at a remote antiquity, and seem to be coeval with these remains. One hy for instance, runs for half-a-mile from north west to south east; it is four feet high, and has a ditch upon each side of it. Were there no other reasons for ascribing these monuments to a period of the highest antiquity, and counecting them (p. 38) with services of a religious character, this simple fact would of itself teud to show that these stones were erected for a sacred purpose. Thus we find at Avebury the Fosse is within the vallum. And I was informed by the late Sir Richard Hoare that, from observations he had made upon several British works in Wiltshire, the Fosse within the vallum invariably distinguished a religious work from one that was military. At the Arbour Lows, in Derbyshire, the Fosse is within the vallum1.

Note 1. Salopia Antiqua.

A curious tradition has prevailed for nearly a century, and we know not how much earlier, respecting Mitchell's Fold. Tt is fabled that in this enclosure—|

"The giant used to milk his cow, which is represented as being unusually productive, giving as much as was demanded, until at length an old crone tried to milk her in a riddle1 when indignant at the attempt, she ceased to yield her usual supply, and wandered, as the story goes into Warwickshire where her subsequent life and actions are identified as those of the Dun Cow.

Note 1. A "riddle"; a large coarse sieve.

A poem about this legend was printed in volume xvii, pp. 172-3 of these transactions, and a longer account of it the writer quotes from Chapter v. of Miss Bourne's Shropshire Folk-Lore, pp. 39-40.

In times gone by, before anyone now living can remember, there was once a dreadtul famine all about this country, and the people had like to have been clemmed1. There were many more living in this part then, than what there are now, and times were very bad indeed. And all they had to depend upon was that there used to come a fairy-cow upon the hill, up at Mitchell's Fold, night and morning to be milked. A beautiful pure white cow she was, and no matter how many came to milk her, there was always enough for all, so long as everyone that came only took one pailful. It was in this way: If any one was to milk her dry, she would go away and never come again; but so long as everyone took only a pailful apiece she would never be dry. They might take whatever sort of vessel they liked, to milk her into, so long as it was only one apiece she would always fill it. Well, at last there came an old witch, Mitchell hername was. A bad old woman she was, and did a deal of harm, and had a spite against everybody. And she brought a riddle and milked the cow into that, and of course the poor thing couldn't fill it. And the old woman milked her, and milked her, and at last she milked her dry, and the cow was never seen there again after. Folks say that she ran off into Warwickshire like a crazy thing, and turned into the wild dun cow that Guy, Earl of Warwick killed; but anyhow they say she was sadly missed in this country, and many died after she was gone, and there's never been so many living about here not since. But the old woman got her punishment. She was turned into one of those stones on the hillside2, and all the other stones were put up round her to keep her in, and that'h why the place came to be called Mitchell's Fold, because her name was Mitchell, you see. There used to be more stones than there are now, but they have been taken away at one time and another. It's best not to meddle with such places. There was a farmer lived by there, and he blew up some of them and took away the pieces to put round his horsepond, but he never did any good after. This story is very well-known among the cottagers and others in that part of Shopshire, but it is not often told in full detail. Variations of it, of course, are current. The witch is sometimes said to have been buried in the middle of the circle of stones, which were raised around her to "keep her in," i.e., to prevent her coming out again as a ghost It is another trace of the belief that the mountains were inhabited, and the mysterious monuments on them erected by a race of giants. "Fold," in Shropshire, means a farmyard. I suspect the name Mitchell was originally given not to the witch, but to the owner of the wondrous cow, and that Mitchell's Fold simply means the farmyard in which he milked her.

Note 1. i.e. nearly starved to death.

Note 2. See Folk-Lore Record, Vol II.

![]() Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

These lengthy quotations show that. Mitchell's Fold is one of the most important prehistoric remains in the district, and the legend connected with it is but second to the Bagbury bull in interest.