Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Text this colour are links that are disabled for Guests.

Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page. Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

Newgrange Passage Tomb is in Boyne Valley, Prehistoric Ireland.

Annals of Ulster. 534 The drowning of Muirchertach Mac Erca i.e. Muirchertach son of Muiredach son of Eógan son of Niall Naígiallach in a vat full of wine on the hilltop of Cleitech [Map] above Bóinn.

In 534 Muirchertach mac Muiredaig High King of Ireland was drowned in a butt of wine. The Annals of Ulster report ... The drowning of Muirchertach mac Muiredaig High King of Ireland in a vat full of wine on the hilltop of Cleitech above Bóinn ie at Newgrange Passage Tomb [Map].

Several Observations Edward Lyhwd. We continued not above three Days at Dublin, when we steer'd our Course towards the Giants Causway. The most remarkable Curiosity we saw by the way, was stately Mount at a Place called New Grange [Map] necar Drogheda having a number of huge Stones pitch'd on end round about it, and a singe one on the Top. The Gentleman of the Village (one Mr Charles Campbel) observing that under the green Turf this Mount was wholly composed of Stones, and having occasion for some, employ 'd his Servants to carry off a considerable Parcel of them; till they came at last to a very broad flat Stone, rudely Carved, and placed edgewise at the Bottom of the Mount. This they discovered to be the Door of a Cave, which had a long Entry leading into it.

Philosophical Transactions 335 Section 4. We continued not above three Days at Dublin when we fteer'd our Courfe towards the Giants Canfway. The mott remarkable Curiofity we faw by the way was a ftately Mount at a Place called New Grange [Newgrange Passage Tomb [Map]] near Drogheda; having a number of huge Stones pitch'd on end round about it and a fingle one on the Top. Continues:

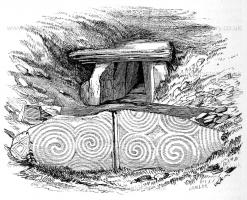

Mona Antiqua Restauranta 310 Letters. I also met with one monument in this kingdom very singular. It stands at a place called New-Grange near Drogheda [Map]; and is a mount or barrow of very considerable height, encompassed with vast stones pitched on end round the bottom of it; and having another lesser standing on the top. This mount is all the work of hands, and consists almost wholly of stones; but is covered with gravel and green swerd, and has within it a remarkable cave. The entry into this cave is at bottom, and before it we found a great flat slone, like a large tombstone, placed edgewise, having on the outside certain barbarous carvings, like snakes encircled, but without heads. The entry was guarded all along on each side with such rude stones, pitched on end, some of them having the same carving, and other vast ones laid a-cross these at top. The out-pillars were so close pressed by the weight of the mount, that they admitted but just creeping in, but by degrees the passage grew wider and higher till we came to the cave, which was about five or fix yards high. The cave consists of three cells or apartments, one on each hand, and the third straight forward, and may be about seven yards over each way. In the right-hand cell stands a great bason of an irregular oval figure of one entire stone, having its brim oddly sinuated or elbowed in and out; and that bason in another of much the same form. Within this bason was some very clear water which dropped from the cave above, which made me imagine the use of this bason was for receiving such water, and that the use of the lower was to receive the water of the upper bason when full, for some sacred use, and therefore not to be spilled. In the left apartment there was such another bason, but single, neither was there any water in it. In the apartment straight forward there was no bason at all. Many of the pillars about the right-hand bafon were carved as the stones above-mentioned; but under feet there was nothing but loose stones of any size in confusion; and amongst them a great many bones of beads and some pieces of deers horns. Near the top of this mount they found a gold coin of the emperor Valentinian; but notwithstanding this, the rude carving above-mentioned makes me conclude this monument was never Roman, not to mention that we want history to prove that ever the Romans were at all in Ireland.

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

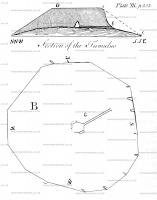

Archaeologia Volume 2 Section XXXV. In PI. XX. the figure B gives the plan of the base [of Newgrange Passage Tomb [Map]] drawn according to Mr. Bouie's stations in measuring it; but you must understand, that the periphery of the real figure is curvilinear, not rectilinear. This base covers about two acres of ground. C is the plan of the cave and of the gallery leading to it; as it bears 240 N. W. D is the section of the pyramid, and of the ground on which it stands projected from a medium of the various numbers I have received. The whole is laid down by a scale of 84 feet to an inch.

Archaeologia Volume 2 Section XXXV. 21st June 1770. A Description of the Sepulchral Monument at New Grange [Map], near Drogheda, in the County of Meath, in Ireland. by Thomas Pownall, Esq; in a Letter to the Rev. Gregory Sharpe, D. D. Master of The Temple. Read at the Society of Antiquaries, June 21, 28, 1770.

Beauties of the Boyne. When we first visited New Grange [Newgrange Passage Tomb [Map]], some twelve years ago, the entrance was greatly obscured by brambles, and a heap of loose stones which had ravelled out from the adjoining mound. This entrance, which is nearly square, and formed by large flags, the continuation of the stone passage already alluded to, is now at a considerable distance from the original outer circle of the mound, and consequently the passage is at present much shorter than it was originally, if, indeed, it ever extended so far as the outer circle. A few years ago, a gentleman, then residing in the neighbourhood, cleared away the stones and rubbish which obscured the mouth of the cave, and brought to light a very remarkably carved stone, which now slopes outwards from the entrance. This we thought at the time was quite a discovery, inasmuch as none of the modern writers had noticed it. The Welsh antiquary, however, thus describes it: — "The entry into this cave is at bottom, and before it we found a great flat stone, like a large tomb-stone, placed edgeways, having on the outside certain barbarous carvings, like snakes encircled, but without heads."

This stone, so beautifully carved in spirals and volutes, as shown in the graphic illustration upon the opposite page, is slighty convex, from above downwards; it measures ten feet in length, and is about eighteen inches thick. What its original use was, — where its original position in this mound, — whether its carvings exhibit the same handiwork and design as those sculptured stones in the interior, and whether this beautiful slab did not belong to some other building of anterior date, — are questions worthy of consideration, but which we have not space to discuss.

Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 1860 V7 Pages 145-191. The first tumulus which I adduce is in the sister kingdom of Ireland, and is generally known in that country as "New Grange [Map]." It is one of four great sepulchral mounds, situated on the banks of the Boyne, between Drogheda and Slane, in the county of Meath, and which have been not inaptly termed "the Pyramids of Ireland." It is the only one of the four, whose interior has been exposed to human curiosity, but there is every reason to believe that if explored, the others would be found similar in nature to the one in question. I extract the particulars of it from the second vol. of Archaeologia, and the Dublin Journal of March 1833, corroborated by the evidence of my father, who visited it, and made a personal inspection of the interior in 1848.1 It is now (as the learned antiquary Governor Pownall tells us) but a ruin of what it originally was, though it still covers two acres of ground, and has an elevation of about 70 feet; but its original height was not less than 100 feet, as it has been used for ages as a stone quarry, for the making and repairing of roads and the erection of buildings in the neighbourhood. It is formed of small stones, covered over with earth, and at its base was encircled by a line of stones of enormous magnitude, placed in erect positions,2 and varying in height from four to eleven feet above the ground, and supposed to weigh from ten to twelve tons each: these stones as well as those of which the grand interior chamber is built, are not found in the neighbourhood of the tumulus, but have been brought hither from the mouth of the river Boyne, a distance of seven or eight miles. The interior of the tumulus, was accidentally made known in the year 1699, when a Mr. Campbell, who resided in the neighbouring village, in carrying away stones from it to repair a road, discovered the entrance to a gallery or passage leading into a sepulchral chamber. This entrance was about 50 feet from the original side of the Pyramid, and is placed due South, and runs Northward: the length of this passage to the entrance of the chamber is about 58 feet, its breadth and height gradually narrowing till at about 18 feet from the entrance it reaches a stone which is laid across in an inclined position, and which seems to forbid further progress: beyond this, the gallery immediately expands again to the width of three feet, and to the height of from six to ten feet at the entrance of the dome. The chamber is an irregular circle, about 22 feet in diameter, covered with a dome of a bee-hive form, constructed of massive stones laid horizontally and projecting one beyond the other, till they approximate and are finally capped with a single one: the height of the dome is about 20 feet. The chamber has three quadrangular recesses, forming a cross, one facing the entrance gallery, and one on each side: in each of these recesses was placed a stone urn or sarcophagus, of a simple bowl form, two of which remain to this day: of these recesses the East and the West are about eight feet square, the North is somewhat deeper. The entire length of the cavern from the entrance of the gallery to the end of the recess is 81 feet 8 inches. The stones of which the entire structure consists are of great size, viz., from 12 to 18 feet long by 6 broad; a great number of the stones within the chamber, as well as in the gallery, are carved with spiral, lozenge-shaped, and zig-zag lines, and in the West chamber there are marks, which have been supposed, though perhaps without reason, to be an alphabetic inscription. That this large tumulus was constructed "as a tomb or great sepulchral pyramid" and that the "oval granite basins originally contained human remains" admits of no doubt: and as to its age, by most of the learned and intelligent modern archaeologists it is referred to the most remote period of Celtic occupation, and far beyond the time of the invasion of the Danes, to which people, like so many other Irish antiquities, it has been sometimes attributed; indeed it is generally supposed to be coeval with, by some to be even anterior to, its brethren on the Nile."3 Such is the remarkable tumulus of New Grange in Ireland, apparently the very counterpart of Silbury: and I have been thus minute in giving all the particulars I could glean, and especially the exact position, with reference to the points of the compass, of the chambers and gallery, because I am not without hopes that they may hereafter be useful to some future investigators of Silbury which perhaps may be found to contain similar treasures.

Note 1. See Mr. Edward Lhwyd's description of it, in a letter to Mr. Rowlands at the end of Mona Antiqua; and that by Dr. Thomas Molineux, published first in the Philosoph: Transactions No. 335 and 336, and afterwards in his discourse on Danish forts in Ireland: above all, see Governor Pownall's description in the Archaeologia, vol. ii. pp. 236 — 275. Also Journal of Archaeological Institute, iii. 156. Stukeley's Itinerarium Curiosum, plate in vol. ii. p. 43. Dublin Penny Saturday Journal, vol. i. p. 305.

Note 2. In the Salisbury vol. of the Proceedings of the Archaeological Institute in 1849, p. 74, Dean Merewether in speaking of Silbury, says, "It is remarkable, though I have not seen it noticed by former writers, that the verge of the base is set round with sarsen stones, three or four feet in diameter and at intervals of about eighteen feet; of these however, only eight are now visible, although others may be covered with the detritus of the sloping sides of the tumulus, and overgrown with turf." This is clearly a mistake, though it is astonishing how the Dean, usually so careful, fell into such an error, for there is, and there has been for very many years, but one small stone visible on the Northern side of the base. [See Mr. Long's "Abury Illustrated" in Wiltshire Magazine, vol. iv. p. 339.]

Note 3. Compare Mr. Scarth's account of this tumulus in his very able paper on "Ancient Chambered Tumuli," published in the 8th vol. of the Proceedings of the Somersetshire Archaeological and Natural History Society: Taunton, 1859, pp. 24—27.

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Llewellynn Jewitt 1870. One of the most important in size, as well as in general interest, is the one at New Grange [Map], county Meath. "The cairn, which even in its present ruinous condition measures about seventy feet in height, and is nearly three hundred feet in diameter, from a little distance presents the appearance of a grassy hill, partly wooded; but upon examination the coating of earth is found to be altogether superficial, and in several places the stones, of which the hill is entirely composed, are laid bare. A circle of enormous stones, of which eleven remain above ground1, originally encircled its base. The opening (of which an engraving is shown on fig. 44) was accidentally discovered about the year 1699, by labouring men employed in the removal of stones for the repair of a road. The gallery, of which it is the external entrance, extends in a direction nearly north and south, and communicates with a chamber, or cave, nearly in the centre of the mound. This gallery, which measures in length about fifty feet, is at its entrance from the exterior about four feet in height, in breadth at the top three feet two inches, and at the base three feet, five inches. These dimensions it retains, except in one or two places, where the stones appear to have been forced from their original position, for a distance of twenty-one feet from the external entrance. Thence towards the interior its sides gradually increase, and its height where it forms the chamber is eighteen feet. Enormous blocks of stone, apparently water-worn, and supposed to have been brought from the mouth of the Boyne, form the sides of the passage; and it is roofed with similar stones. The ground plan of the chamber is cruciform; the head and arms of the cross being formed by three recesses, one placed directly fronting the entrance, the others east and west, and each containing a basin of granite. The sides of these recesses are composed of immense blocks of stone, several of which bear a great variety of carvings2. In front of the entrance (fig. 44) will be seen one of these carved stones.

Note 1. These immense monoliths have originally, it is estimated, been upwards of thirty in number, and to have been placed probably ten yards apart. The largest remaining stone stands between eight and nine feet above the ground, and is seventeen feet in circumference. It is estimated to weigh upwards of seven tons. Several of the stones have entirely disappeared, of others fragments remain scattered about.

For an excellent notice of this and other remains, the reader is referred to Mr. W. F. Wakeman's "Handbook of Irish Antiquities," the best and most compact littlework on the subject which has been issued, and one which will be found extremely useful to the archaeological student to which I am indebted for some of the accompanying engravings.

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

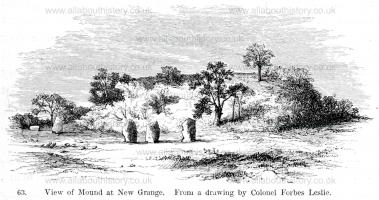

Rude Stone Monuments in all Countries Chapter V. Less than a mile from this one is the larger and more celebrated mound of New Grange [Map]. It is almost certainly one of the three plundered by the Danes 1009 years ago. No description of it has anywhere been discovered, prior to the time when Mr. Llwyd, the keeper of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, mentioned it in a letter dated Sligo, 1699.1 He describes the entrance, the passage, and the side chapels, and the three basins as existing then exactly as they do now, and does not allude to the discovery of the entrance as being at all of recent occurrence, though Sir Thomas Molyneux, in 1725, says it was found apparently not long before he wrote, in accidently removing some stones.2 The first really detailed account, however, is that of Governor Pownall, in the second volume of the 'Archaeologia' (1770). He employed a local surveyor of the name of Bouie to measure it for him, but either he must have been a bungler, or the engraver has misunderstood his drawings, for it is almost impossible to make out the form and dimensions of the mound from the plates published. In the 100 years that have elapsed since his survey was made, the process of destruction has been going on rapidly, and it would now require both skill and patience to restore the monument to its previous dimensions. Meanwhile the accompanying cuts, partly from Mr. Bouie's plates, partly from personal observations, may be sufficient for purposes of illustration, but they are far from pretending to be perfectly accurate, or such as one would like to see of so important a monument.

Its dimensions, so far as I can make out, are as follows: it has a diameter of 310 to 315 feet for the whole mound, at its junction with the natural hill, on which it stands. The height is about 70 feet, made up of 14 feet for the slope of the hill to the floor of the central chamber, and 56 feet above it. The angle of external slope appears to be 35 degrees, or 5 degrees steeper than Silbury Hill, and consequently if there is anything in that argument, it may, at least, be a century or two older. The platform on the lop is about 120 feet across, the whole being formed of loose stones, with the smallest possible admixture of earth and rubbish.

Around its base was a circle of large stone monoliths (woodcut No. 63). They stand, according to Sir W. Wilde, 10 yards apart, on a circumference of 400 paces, or 1000 feet. If this were so, they were as nearly as may be 33 feet from centre to centre, and their number consequently must originally have been thirty, or the same number as at Stonehenge. From Bouie's plan I make the number thirty-two, but this is hardly to be depended upon. From this disposition it will be observed that if the tumulus were removed, or had never been erected, we should have here exactly such a circle — 333 feet in diameter — as we find at Salkeld or at Stanton Drew, an 1 it seems hardly doubtful but that siicli an arrangement as tliis on the banks of the Boyne gave rise to those circles which we find on the battle-iields of England two or three centuries later. Llwyd, in his letter to Rowland, mentions one smaller stone standing on the summit, but that had disappeared, as well as twenty of the outer circle, when Mr. Bouie's survey was made.

Note 1. Rowlands 'Mona Antiqua.' p. 314.

Note 2. 'Philosophical Transactions,' Nos. 335-336.

![]() Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Become a Member via our Buy Me a Coffee page to read more.

Antiquity 2025 Volume 99 Issue 405 Pages 672-688. The 'king' of Newgrange? A critical analysis of a Neolithic petrous fragment from the passage tomb chamber.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24th June 2025.

Abstract: Recent genomic analysis of a skull fragment from Newgrange, Ireland [Map], revealed a rare case of incest. Together with a wider network of distantly related passage tomb interments, this has bolstered claims of a social elite in later Neolithic Ireland. Here, the authors evaluate this social evolutionary interpretation, drawing on insecurities in context and the relative rarity of engendered status or resource restrictions in the archaeological record of prehistoric Ireland to argue that the status of individuals during this period is better understood through unstable identity negotiations. Inclusion in a passage tomb, while 'special', need not equate to a perpetual elite.

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial - Share Alike licence, which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the same Creative Commons licence is included and the original work is properly cited.